Rose Valley Shops

View works from the Rose Valley Shops representing work done by the three ‘shops’ that operated under the aegis of the Rose Valley Association:

Price & McLanahan’s Furniture Shop,

William P. Jervis’ Pottery Shop,

and Horace Trauble’s Rose Valley Press, printing The Artsman.

Work in these shops met the standards of the Rose Valley Association and was marked with varying forms of the Association’s seal, a wild rose superimposed by a “V” and circled by a buckled belt.

Will Price and his extended family along with Hawley McLanahan and his family were the first members of the Rose Valley Association. They made plans for a social center with lectures, plays and concerts, a library, a museum, and a school for children, who, in the words of Hawley McLanahan, would be taught “through the hand to the brain.” They intended to convert water power into electricity for use in the craft shops and the community, and to plant trees to beautify the public and private spaces. All income beyond the stock and fixed expenses would be devoted to the general improvement of the property.

Some income was to be generated by craft production. Although there were many artists and craftsmen among the members of the Rose Valley Association, they did not necessarily make the handicrafts that were marked with the Rose Valley seal. The Association intended to rent space to non-resident artisans who would be allowed to use the Rose Valley seal: a rose with a “V” superimposed and circled with a buckled belt that symbolized fellowship. The firm of Price and McLanahan was the first to lease property from the association, converting the burnt out textile mill on Ridley Creek into housing for a furniture shop. As it happened, the only non-residents were ceramist William Percival Jervis and most of the woodworkers. The furniture, Jervis pottery and of course The Artsman, printed at the Rose Valley Press, bore the Rose Valley seal.

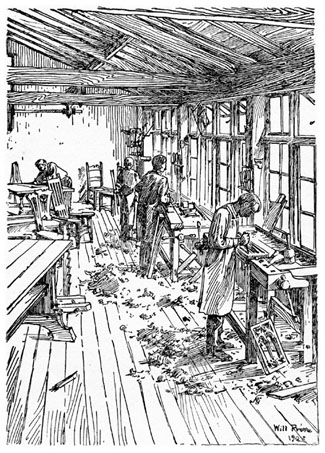

The Furniture Shop

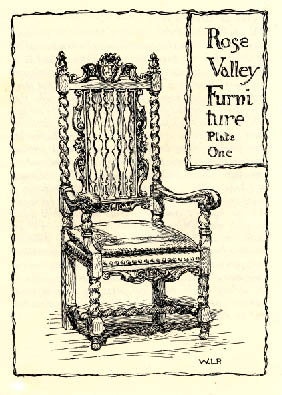

Modern Arts and Crafts movement historians believe the furniture to be the most important part of the Rose Valley experiment. Ironically, Price was having furniture custom made for use in the houses he designed before Rose Valley was founded. Those designs are indistinguishable from the ones used at the shop in the old mill. Even pieces bearing the Rose Valley seal could have been made at Edward Maene’s Philadelphia workshops.

Unlike the studied plainness of the furniture manufactured by Gustav Stickley and Elbert Hubbard, Price designed furniture in a highly decorated Gothic style. Rich American homeowners had a taste for such dark, elaborately carved furniture that began in the 1870s and continued throughout the 1920’s. Like Rose Valley furniture, much of it was hand carved. How, then, could Rose Valley pieces be so closely associated with the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement?

William Morris wrote the primary tenet of the Movement: “have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Certainly Rose Valley furniture was both useful and beautiful. But Will Price too was quite a wordsmith and his writing in The Artsman left no question about how he thought his products embodied the ideals of Arts and Crafts philosophy. Still, Price ran into the same problem that had confounded Morris. Arts and Crafts philosophers made much of the democratic and socialist nature of their utopian visions but, in practice, the production of objects meeting their standard of handcraftsmanship was an expensive and, therefore, an elitist proposition. A mass-produced dining table from Gustav Stickley cost $66 in 1904, putting it well beyond the reach of most Americans; A grand, hand-carved Rose Valley table cost $150. Even so, the Rose Valley order book and the photographs of furniture in the process of being built suggest that the furniture shop was very busy during the few years (1901-1906) it operated.

Jervis’ Pottery

William Percival Jervis was a nationally known master potter. Before coming to work in Rose Valley, he managed the Avon Faience Company and worked at the Corona Pottery. He produced The Encyclopedia of Ceramics and wrote Rough Notes on Pottery, A Book of Pottery Marks and English Potters and American History.

He rented a studio in the Rose Valley guildhall where he created many highly praised pieces marked with the Rose Valley seal. The fanfare that greeted Jervis’ arrival at Rose Valley came at the height of the popularity of art pottery. The process of making artistic pots had become closely identified with the Arts and Crafts way of life, and Jervis announced that his pottery would be simple as befitted the simple life. Even though Jervis may have commuted to his studio from Philadelphia, the idyllic environment of the Valley suited his artistic sensibilities. He wrote:

“Before I came here I had heard something of the Rose Valley Association and of the charm of the place itself, but I had never imagined there were men fortunate enough to pursue their work under such conditions as I found. To lift up your head and look at tree-clad hills instead of brick walls; to hear the murmur of waterfalls instead of the roar of trains or clanging bells of cars; to know that around the hill the river broadened into delicious reaches amidst the shade of the overhanging forest, where birds were encouraged and protected, instead of shot, and where the bright fronds of the fern still showed green amid the reds and crimsons of trailing vines—I think that anyone to whom such things appeal would feel as I do: that work would become a religion, a pleasure. And be sure that when work is a pleasure all that is in a man, be it much or little, is brought out.”

Indeed, some of his pottery designs incorporate the green fern fronds that so attracted Jervis. The glazes he developed at Rose Valley where praised by none other than Louis Comfort Tiffany who pronounced them to be the finest he had ever seen.

Although Jervis produced hundreds of pieces while at Rose Valley, very few are known today. He claimed that the Rose Valley mark would be “impressed in the clay or printed in color.” on his pots. Evidence suggests that much of Rose Valley ceramics was not marked at all. Perhaps these pieces once had a paper label “printed in color,” but no example of the color label is presently known. Other pieces have raised nubs arranged in a circle, which are thought to be represent the stamens of the Rose Valley rose while other pieces are inscribed “W.P. Jervis” or bear a handmade version of the seal. He left his pottery studio in Rose Valley in 1905.