Rose Valley History

If you believe in the

bridge of desire that leads

to Brigadoon and the knight

who fought through thickets

of thorns to rescue Briar Rose,

you will be able

to find Rose Valley,

then and now.

Also in this section:

If you believe in the bridge of desire that leads to Brigadoon and the knight who fought through thickets of thorns to rescue Briar Rose, you will be able to find Rose Valley, then and now. If you don’t know your heart’s desire, you’ll careen right past this legendary village experiencing only frustration and fear from maneuvering an automobile through the gauntlet of blind curves and thrilling hills on a tarmac road that services harried commuters.

Rose Valley now appears to the casual observer to be a tightly clustered group of homes on the outskirts of Media, Pennsylvania. There is no convenience store, no gas station, and no sidewalk, The hidden lanes and private drives do nothing to encourage the curious. Still, the intrepid who find a legal, safe parking spot will notice that the buildings in Rose Valley are very different from those in the surrounding suburban sprawl.

Some, like the Hedgerow Theatre, look like ancient structures from an unknown place and time. Hidden behind overgrown bushes and trees, others look like cottages in a storybook illustration.

There are curious consistencies: most have stucco walls with stone buttresses and colored tiles showing through here and there, and many have red tile roofs. Windows have a distinctive arrangement of panes. The grander houses are secluded at the ends of long drives. Others are so close together that on a warm summer day, neighbors can hold conversations with each other from open bathroom windows and kids can scamper to the hidden swimming pool on paths that wind through adjoining back yards. How did the Rose Valley we see now come to be this way?

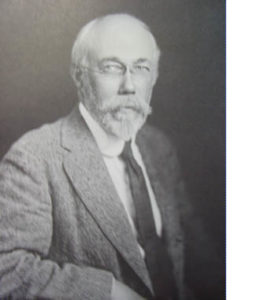

Rose Valley looks the way it does because of the vision of one man, William Lightfoot Price.

See? Even his name has a hint of romance. “Lightfoot” was Will’s mother’s maiden name and can be traced back in Philadelphia Quaker families all the way to William Penn.

The Arts and Crafts movement was part of a larger reaction to the industrial revolution, which began early in the nineteenth century. The invention of the steam engine changed society profoundly. The agrarian/craftsman system that had been evolving for centuries became a factory-based system in less than two decades. Once, all of society in Western Europe and America was devoted to managing the land. Then, suddenly, all but the very rich became slaves to mass production. The land itself became a sort of factory where fuel to fire industrial machinery was gouged from the earth. Coal, gas, oil, and food had to be produced in huge amounts. For a while steam boats, trains and tractors, cast iron buildings, machinery, and furniture, and mass-produced food, clothing, and furnishings seemed quite wonderful. But it didn’t take long for those who had the luxury of time to contemplate life to notice that pollution was blackening every aspect of this new way of life. By the 1850s, designers like Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin had begun to think about the way mass production influenced the quality of life in general and the role of the craftsman in particular.

Byrdcliffe

Roycroft

Stickley

Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, and William Morris codified a philosophy in which machine-made goods were thought to be inferior in beauty. To the Arts & Crafts philosopher, art and utility would give meaning to life if they could be wedded in a process that required imagination, creativity and personal responsibility. They thought mass production lowered the standards of design, workmanship and working conditions for the craftsmen and minimized their contribution to the finished product. Industry polluted and defaced the natural landscape thus reducing the quality of life for all, yet profits from the factory system went only to improve the quality of life of the factory owner.

In the United States, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Charles Elliot Norton among others helped formulate the Arts and Crafts philosophy. Philadelphia became the geographical center of the Movement when the Centennial Exposition opened in Fairmount Park. Maria Longworth Nichols attended the fair and Mary Louise McLaughlin exhibited her work at the Woman’s Pavilion. The two women went home to Cincinnati where they started their own art potteries. More significantly for Rose Valley, Philadelphia architect Frank Furness designed many of the installations at the fair and thus influenced the exposition’s overall style. Furness is now seen as an early proponent of ideas that form the core of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Among the Furness students who established a nationally important country-house style were Frank Miles Day and William Lightfoot Price.

Will Price was becoming a leading figure in a new social movement. Price and his wife, Emma, were free-thinking Quakers whose Overbrook, PA home became a meeting place for a group who gathered to discuss art, economics and social justice. This group decided to experiment with their ideas by establishing a single tax community. In 1900, Frank Stephens, Joseph Fels and William Price founded Arden, Delaware. In 1901,Will Price purchased eighty acres of land surrounding what had been Rose Valley Mills and immediately began to design and construct a new community based on the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. The Rose Valley Association was established on July 17, 1901.

Although the establishment of Rose Valley predates most other Arts and Crafts communities in America by several years, the idea was already in the air. Boston, Chicago, New York and Minneapolis all had non-resident clubs to promote their ideals. Ralph and Jane Radcliffe-Whitehead were building the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony near Woodstock, NY and Elbert Hubbard was building the Roycroft Shops in East Aurora, NY. The latter was primarily a commercial venture as was Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman G. furniture enterprise. Each organization was characterized by their founders’ unique interpretation of Arts and Crafts ideals. Will Price modeled Rose Valley on the utopian English village described by William Morris in News from Nowhere.